Chinese Scholars on Life Today: Two Generations, Two Views

Professor Zhang Ming from Chinese Academy of Social Sciences recommends strategic effort, free will & time optimization; while his student holds a different view

As mid-November arrives, China’s “Autumn Recruitment” season – the most crucial hiring period for new graduates – is in full swing. Looking back at this time last year, I remember the dizzying demands of my final year: not just searching for jobs but balancing two internships, a part-time gig, classes, and a thesis. My classmates were no better off. A friend once vented to me: “I’ve been doing interviews for over a month now – seven or eight rounds – and I only met one person face-to-face! The rest were with AI, and none of them came through.”

It’s clear that a new era has come. As someone who has lived through it, I feel compelled to capture something of this moment.

In the post-pandemic era, the economic downturn has led many companies to cut back on hiring, while university enrollments keep rising. This leads to a stark imbalance in the job market, where companies claim they can’t find suitable hires, yet graduates feel unable to secure positions.

It’s no wonder, then, that terms like “involution” (内卷) and “lying flat” (躺平) have gained traction, encapsulating the sentiments of a generation facing a complex reality.

In today’s newslwtter, I’m excited to share views from two generations of Chinese scholars on navigating societal pressures and personal growth. Their contrasting views reflect the generational divides in facing today’s challenges, offering a glimpse into what it means to thrive – or simply survive – in modern China.

The piece of article was originally published on the WeChat public account Zhang Ming's Macro-Financial Research张明宏观金融研究. This piece presents the opinions of Professor Zhang Ming and his student, Professor X, from a renowned university, on navigating life’s purpose amid social pressures.

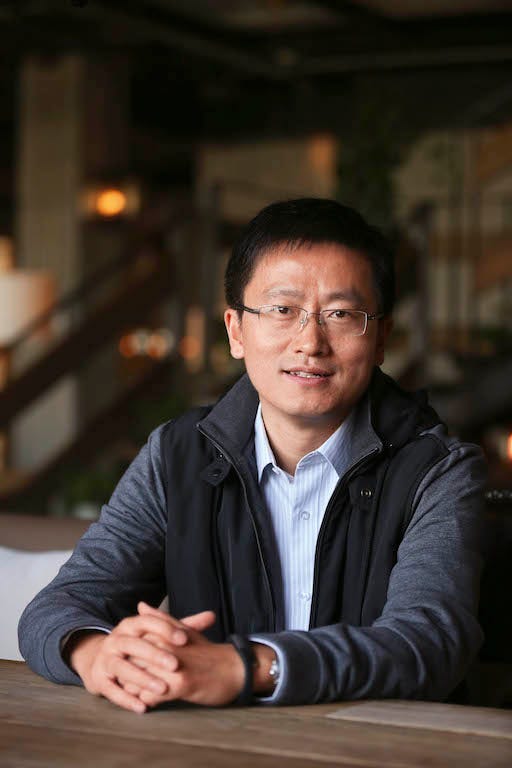

Prof. Zhang Ming 张明 currently serves as a senior fellow and the Deputy Director of the Institute of Finance & Banking at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). From 2017 to 2020, he worked as the chief economist of Ping An Securities Co., Ltd. Notably, he also worked as the Vice Mayor of Mianyang city of Sichuan Province from 2021 to 2022. His research covers international finance and Chinese macro-economy.

Below are my translation.

如何在内卷与躺平的时代里过好自己的人生?

How to live our lives in an era of "involution" and "lying flat"?

Note: Recently, I shared an article in my student group titled A Life Focused on Cost-Effectiveness May Not Be Worth It After All, along with the following comment: "This piece truly speaks to me. Compared to our younger days, today’s youth seem to lack a bit of the edge, boldness, and diversity we once had. Pursuing a cost-effective life is, in essence, a beautifully crafted shackle. When you're young, you should take risks and do some foolish things - that's how we truly grow." To my surprise, this article sparked an intense discussion within the group, gathering hundreds of responses in just one morning. Among them, a particularly noteworthy view came from Student X, who is also a long-time debate partner of mine and now a professor at a prominent university. In this article, I’ll first share his perspective, and then provide my response. To preserve the authenticity of the discussion, I’ve made no edits. The accompanying image was taken at the café by the Forbidden City.

I. Student X’s Perspective

The recent post about declining marriage rates reflects how many born in the '90s and 2000s feel walled in by life. I may have missed the last train, but I’m not completely left behind. Compared to the vibrant spirit of the past, when life was poorer, today’s seeming prosperity feels empty, wearing down young people day by day. They can’t understand why there’s always more to study, why work and tasks never seem to end, or why money is always tight. After years of effort, healthcare is still unaffordable, and even after a lifetime of striving, a safe and stable education for their children isn’t guaranteed. Despite high average incomes, people still have to spend so much on potentially carcinogenic food.

Young people see things differently than middle-aged people do. Those who have already been through this may feel that even failure is a path forward, possibly leading to greater achievements. But young people fear that failure could mean the end - or even life or death. Growing data supports their fears, making this situation all the more concerning. I have taken many detours myself; while I didn’t walk away empty-handed, I certainly wasted a lot of time. Now, I’m just barely getting by each day - not expecting wealth or luxury, but enough to keep going. But if young people today were to follow the same winding path I did, they might not make it, or they might only survive at the cost of their dignity. Competition has escalated to the point where only the top few percent can secure a job with even a hint of social respect. This issue has moved far beyond mere "elegance" or "refinement." No one wants to live without dignity.

It’s not about income levels as much as the extremely poor social security. Public service attitudes are far worse than they were in the past, even though public infrastructure may look more developed. Issues in education, healthcare, and food safety are worsening, and it’s becoming harder than ever to find a safe and secure living environment.

Looking back, these issues have always been present - some were even more severe in the past. It’s just that, for a time, rapid economic growth shifted our attention away from them. I wrote a paper that explores the impact of wealth disparity on consumption and investment, finding that it is rooted in psychological perception. People's sense of utility is shaped by comparisons: with their own past, with others in non-linear ways, and with the growth rate of themselves and those around them. As long as one’s own growth is fast enough, the widening income gap won’t be a concern. In other words, the more developed an economy, the larger the income disparity people can tolerate, and they may not even perceive it as a problem. Conversely, even if income disparity improves, people may still feel that income distribution is worsening.

So, these issues existed in the past, and they remain today. As an old Chinese saying goes, "the wise follow what is beneficial.君子择善而从" Our role is to continuously seek out paths that align with the genuine needs of the times, even amid uncertainty. There’s no need to be fixated on just one path.

When life is on an upward trajectory, we feel optimistic; on a downward slope, we feel despair; and on a flat path, we feel lost. The first derivative determines economic fundamentals, while the second derivative determines expectations - it’s not tied to absolute value or height.

To be honest, teaching and studying are all I have left to do. If I had any other way to sustain a decent life, I wouldn’t have become a university teacher. This year, I’ve been unusually idle. The work I once handled now feels too demanding as my energy fades. I'm reaching a point where even that is almost impossible, facing middle age without finding an opportunity for transition.

Banks have indeed offered good benefits in recent years, which is why most of our recent graduates are now flocking to them. But early career stages in banking are truly undignified.

Food is a major concern. I feel my health declining. I’ve been on high blood pressure medication for over six months, and my blood sugar levels are raising red flags. My cholesterol is fine, but I’ve had a fatty liver for a decade. Actually, my mental stress has significantly eased since last year - I’ve become more laid-back and let things slide much more often.

Haha, we’ve been sharing a lot of negative energy in the group. Don’t let us mislead you - life still has a lot of potential. Just remember: don’t stay in Beijing or Shanghai, don’t get married or have kids, and don’t become a university professor.

Our generation caught the tail end of an optimistic era, and we still believe that those with ambition can achieve their goals. Our parents’ generation lived by this as well. But when we talk with young people and students now, it's a different story. For many young people, the prospect of making life-long choices feels indifferent, even meaningless. This trend is increasingly common among younger students - they lose curiosity about learning early on. Those born in the '90s and 2000s missed out on the "strive and succeed" era, so our optimistic outlook doesn’t resonate with them. Life has taught them different lessons than what we preach. University students aren’t the only ones reluctant to study; it’s widespread even in primary and secondary schools. There’s a lack of curiosity, a lack of joy, and a sense of spiritual emptiness. Finding a hobby might sustain them for a while, but after that, they often slip back into despondency.

I find it incredibly challenging to step into the lives of today’s young people, especially if it means letting go of the busyness we’ve become so accustomed to. In the past, there was a period of rapid expansion in education and industry that created opportunities. Our parents’ generation was able to seize those chances. Even my ability to study and teach isn’t entirely due to personal effort; it’s largely a product of that era’s educational expansion. This is a completely different landscape from Professor Zhang’s generation, where attending college or pursuing a graduate degree was far less accessible.

Nowadays, pursuing an education is common, but the rewards are minimal. As individuals, we should certainly keep striving. But in the context of this era, many young people are choosing to pause, to “let things go,” to move away from major cities like Beijing and Shanghai, to decline marriage and children, and to step away from academic and research careers. These are not choices to criticize; in fact, they are reasonable responses to the times. If someone, as an individual, still wants to work hard, they should continue with the competitive grind.

Think of it this way: making money largely depends on luck, but you still need to place a bet; that’s the cost. Without placing a bet, you’ll never encounter luck. Investments may involve losses, but the impact varies greatly with scale: losing 30 million out of a billion, three million out of ten million, or 300,000 out of a million are very different situations. Even Buffett experiences declines, yet it doesn’t affect his long-term strategy. We have an enormous need for liquidity and lack long-term capital. Not only that, but we also lack the energy for long-term commitments. If you think of your time as investment capital, most of it goes toward short-term gains. If a job can offer even a bit of long-term value, that’s rare - and perhaps the only real advantage of teaching.

Is this era less friendly to young people than the '80s and '90s? My answer is YES. This isn’t just my personal view; it’s a perspective shaped by observing today’s realities.

First, intergenerational mobility has declined. On the surface, mobility in the '80s and '90s was limited, but it actually exceeded what we see today. The benefits of the first wave of reform and opening up didn’t reach those born in the '30s and '40s; instead, it primarily benefited those born in the '50s and '60s. The second wave largely bypassed the '40s and '50s, benefiting those born in the '60s and '70s. Since the turn of the century, aside from a few standouts in emerging sectors, economic growth has primarily benefited those born in the '50s, '60s, and '70s, not those born in the '80s and '90s. This is the inevitable result of an economy shifting from labor-driven to capital-driven growth. Today, not only has social mobility slowed, but intergenerational mobility has also worsened. The little mobility that remains tends to occur within each generation rather than across generations. In other words, people’s competitive options now only involve outperforming peers and waiting for their age group’s turn, rather than the earlier belief in the power of determination.

Second, although today’s rules of competition are more transparent, this transparency reveals deeper inequalities in opportunity. The '80s and '90s indeed had widespread privilege and reliance on connections, perhaps even more than today. That era’s slogan of New Oriental (a well-known educational training institution in China) - “To Find hope in Despair在绝望中寻找希望” could only succeed because competition was limited and entry barriers were low. In other words, as long as you worked hard, you had a chance to compete, even if the playing field wasn’t fully fair. Today, while the rules are more transparent and fairer in theory, opportunities in education and employment come with clear price tags. But the competition has intensified, and the bar for entry has risen sharply. Regrettably, many simply don’t qualify to participate. For example, my parents, as average teacher-training students, could enter graduate programs, pursue PhDs, and leave their rural home purely through self-study, despite never having formally studied English. Now, that would be nearly impossible. In those days, if a “professional exam” required one book, it meant studying that book alone; today, the requirements are vastly more complex. The selection process we use for students now far exceeds what they actually learn in school, and for employment interviews, it’s even tougher. We can no longer even guarantee a basic job for a master’s graduate. This growing inequality of opportunity means that people’s backgrounds, access to training, and opportunities for growth vary widely, leading to an unequal competition under seemingly equal rules. Compared to the vague efforts of the past, today’s clear-cut competitive landscape, with its sharp disparities, feels much more discouraging.

Third, the link between self-fulfillment and the pursuit of a materially comfortable life has weakened. Yes, today’s youth live in an era of material abundance, generally free from hunger and with basic security. But in the '80s and '90s, as people pursued material well-being, they also found a sense of self-worth. Each improvement in life brought a greater sense of satisfaction. Now, it’s difficult to draw a connection between the two. On one hand, people feel constrained. Basic needs may be met, but when considering lifelong costs like raising children and retirement, most families lack any financial flexibility, and achieving material self-worth has become difficult. On the other hand, as mobility declines, people are left to wait in place, offering little chance for self-fulfillment. Undoubtedly, those born in the '80s and '90s will gain as those born in the '60s and '70s retire, inheriting power and material wealth, leading to a more comfortable life. However, this waiting period coincides with their most vibrant and driven years. From this perspective, it’s hard to argue that today’s era is more welcoming to young people.

Of course, we’ve never been opposed to hard work, nor do we blame every frustration on the times. We’re simply saying that young people deserve more understanding - it’s okay if they choose to “lie flat,” if they don’t want to follow our path of relentless striving, or if they lack the same drive. I consider myself fortunate to have experienced both worlds: I witnessed the sweeping tides of the past alongside my parents, and I also spent the last decade or so transitioning into the current era after graduating from university. I saw the vibrancy before the subprime crisis and the stagnating wages that followed. It’s unwise to dismiss the value of hard work or deny the impact of the times. But it’s worth considering that different eras call for different approaches to striving. Perhaps today, the best strategy for those born in the '80s and '90s is to take a step back, prioritize health, and reserve the hardest work for after fifty.

II. My Response

I was in meetings all day and didn’t have time to join the group discussion. I didn’t expect such a lively debate, and as always, Student X has taken on the role of conversation leader. Here are my personal thoughts for your reference:

I don’t deny the issues everyone mentioned. These challenges certainly exist, and I’ve discussed them in my book, Macro China《宏观中国》. I believe the analysis and recommendations there on the decline in social mobility and how to address it are still relevant and reliable.

However, today’s discussion centers on whether, despite all the changes in the broader environment, there is still room for individual effort and mobility. Let’s not forget that throughout Chinese history, many periods of hardship have emerged. The choice between going with the flow or pushing forward has always been available on a personal level. Sometimes, the most challenging environments produce the most remarkable individuals, and these figures don’t necessarily come from privileged backgrounds.

Has society truly become more unequal and unfriendly toward young people compared to the 1980s and '90s? I think we should be careful about drawing that conclusion. Many hidden privileges and rights existed back then, unknown to outsiders, and intergenerational mobility wasn’t as strong as people tend to imagine. For example, if you were born into a rural or low-income urban family, changing your fate through personal effort was challenging, especially if you weren’t exceptionally talented. In some ways, I believe today’s society offers more pathways. However, modern media amplifies income disparity and individual circumstances. Even I sometimes feel a bit discouraged when watching videos of attractive people living lives of luxury without having to work for it. But there is often a significant gap between online portrayals and reality.

In sharing this article today, I genuinely wanted to discuss whether, for an ordinary young person in today’s environment, it’s rational to follow the “groupthink” and join this endless race. Does it truly make the best use of personal resources? Consider that this young person comes from an average family, without a strong background. Is it truly optimal to enter the race for grades, spend precious college years striving to be in the top 10% just to secure a place in a graduate program? Is it wise to take on high risks and loans to buy a “school district house” to ensure their child doesn’t “fall behind at the starting line”? Is it truly beneficial to enter hyper-competitive universities where tenure-track evaluation or postdoctoral qualifications are required? Are they living the life they genuinely want, or just fulfilling others’ expectations? My answer is that ordinary individuals do have free will and the freedom to choose. We can still live the life we truly want, as long as we resist being swept up by “collective thinking” and avoid being passively trapped in an “information bubble.” There isn’t just one path up the mountain, nor only one summit in life.

I firmly believe that, in this era of collective “involution,” young people who can think independently and see through mainstream games can allocate their time and resources more effectively. By developing unique strengths, they can create a fulfilling life in other ways. But “fulfilling” doesn’t necessarily mean a big house (and certainly not a school district house), high salary, or societal “success.” Rather, it’s about setting personal goals based on one’s understanding of the world and working toward them. Of course, there are basic standards - such as being able to support one’s family and living a life of “dignity.” However, we should remember that even the idea of “dignity” is often shaped by others’ expectations.

If I were currently an undergraduate at the University of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, coming from an ordinary family in a small town with just enough support to get me through college - and with everything else dependent on my own efforts - here’s how I’d plan my college years:

First, I’d set a target of around 80% in each course, based on my abilities. Anything higher wouldn’t be worth the extra effort, especially since I know postgraduate recommendation isn’t in the cards for me.

Second, I’d use my college years to build a broad foundation in reading. I’d seek out reputable reading lists from diverse, trusted sources, read all the overlapping books, and take thorough notes to develop a foundational understanding of the world.

Third, I’d use my vacations for internships within my reach. They wouldn’t just be about completing tasks or making money; I’d focus on understanding the organizational structure, learning from standout employees, gaining insight into various industries, and adding to my understanding of society. Over a few internships, I’d gain a general sense of various fields.

Fourth, I’d spend about a year preparing for the graduate entrance exams. If I succeed, I’d continue my studies; if not, I’d shift my focus to finding a job.

Fifth, I’d make sure to use my time in college to build physical fitness and pick a lifelong sport, as health is fundamental.

Sixth, I wouldn’t get involved in students' union or other similar roles.

Seventh, I’d keep my job search open to second-tier cities like Chengdu, Wuhan, or Hangzhou, where industries have room for growth - not just Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, or Shenzhen.

Eighth, I wouldn’t rush to buy property, given the changing real estate landscape.

Ninth, I’d let relationships develop naturally. I believe there are people out there open to being with someone from a small town who has direction and steady ambition.

Tenth, for the next 20 to 30 years post-graduation, I’d keep investing in myself through reading, reflecting, staying active, refining my skills, and building my career.

Eleventh, I’d manage my material desires, avoiding impulsive debt or quick-money schemes.

Twelfth, I’d carefully build my network, choosing like-minded friends, connecting with people who are more capable than I am, and keeping close to mentors who offer genuine, constructive feedback.

Thirteenth, I’d focus on becoming who I truly want to be, rather than conforming to others’ expectations. This way, I’d see setbacks as opportunities to experience life’s different stages, rather than as disappointments. I wouldn’t get caught in the relentless “grind,” and, regardless of where I end up, I’d continue to follow my interests and put in the effort, trusting that the outcomes will come in time. Above all, I wouldn’t allow myself to fall into despair.

I firmly believe that while the external environment is one thing, personal effort - and how we apply it - is another. We shouldn’t use changes in the external environment as an excuse for a lack of effort or for misguided effort, nor should we attribute the inevitable lack of success resulting from “lying flat” to the environment. It’s easy to conclude that “the world is just like this, and personal effort is meaningless.” In my student groups, I consistently share messages of positivity. Many of my friends come from humble backgrounds, without family support, yet they have established themselves in major cities and achieved significant success in their fields through their own hard work. Among them are people born in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, and even the ’90s. This demonstrates that it’s possible to break cycles, rise above one’s original circumstances, and reshape one’s destiny through personal effort. Young people shouldn’t be blindly optimistic, but neither should they be discouraged. At its core, economics teaches us that individuals, even under resource constraints, can maximize their well-being over time. If you do well enough, you might even change those constraints. But if you choose to lie flat and refuse to strive, or if you get swept up in “involution” that ultimately leads to mediocrity, then there’s little ground to criticize the times, as you’ve never truly spent decades pursuing your chosen goals with sustained effort. I firmly believe in an individual’s “freedom of choice.”

The reason I’ve written so many “inspirational pieces” over the years is that this belief resonates deeply with me, and it’s how I live my life. While I may not have achieved remarkable success, I feel I’ve lived a genuinely fulfilling half-life. Coming from a modest working-class family in a small town, I found a path that suits me. For the past 25 years since graduating from college, I’ve been on this journey: enriching my soul through reading, strengthening my body through exercise, enhancing my skills through work, and building a network through sincere connections with friends. I aim for steady, daily progress without being overly focused on the outcomes. Many achievements lose their significance the moment they’re reached - a professorship, a published paper, a house. True happiness lies in the journey of striving, in the positive influence we have on others (especially the young), and in knowing that, through our own efforts, we’re making the world a bit better. I hope my students find confidence in these words, learning to embrace the world - whether it’s getting better or worse - and making the most of the beauty life offers through their own efforts. (I increasingly feel that mental fulfillment is more important than material abundance.) I also hope they work to improve the world around them, even in small ways. Living idly, lying flat, and complaining in pessimism is one way to live. But so is a life filled with positivity, effort, and active engagement. Why not choose the latter? True optimism means recognizing the darkness in the world yet still fighting hard, continually bringing positive energy to those around you. I don’t see life as a gamble on luck; I believe in my own efforts. And even if my efforts don’t yield the desired results, the act of striving itself brings me joy. We may not be able to choose our era, but we can certainly choose how we live our lives.

Recently, during a lecture, a young student asked me, “Professor Zhang, at this stage in your career, what would you say is your core competitive advantage? And do you think AI will eventually replace you?” I didn’t get a chance to answer at the time. After reflecting on it, I realized that now, approaching fifty, if I still have a core set of strengths, they might be as follows:

First, I’ve developed a systematic framework for analyzing macroeconomic and international financial issues, which I continuously refine based on outcomes and insights.

Second, I have a broad range of life experience. I’ve worked in think tanks, academia, and government roles, and within financial markets, I’ve been on the sell side (as chief economist at a brokerage), the buy side (as a private equity fund manager), and as an intermediary (as an auditor), collecting many stories along the way.

Third, I’ve read around 2,000 high-quality books, giving me a broad base of knowledge.

Fourth, I’ve honed my speaking skills and continue to work on refining them.

Fifth, I manage my physical health with discipline and have cultivated lifelong interests in basketball and fitness. I recently started running as well.

Sixth, I’ve developed an upbeat and humorous personality and built a social circle that’s supportive, fun, and driven. My personal standard is to be unique, engaging, and warm-hearted.

I aim to do something meaningful every day. If a day ends up feeling dull or uninspiring, I’ll close it with 30 push-ups and 50 squats - after all, no one can stop me from exercising.

In short, I don’t believe AI could easily replace me, and I remain an open, collaborative attitude toward working alongside it. If there’s one thing in this world worth competing for, it’s our health. Here’s to that pursuit - let’s all keep striving. Enditem