James Liang Calls for Four-Day Workweek in China

While idealistic, it could at least help the country better implement the five-day workweek

Today's newsletter features an article by Dr. James Jianzhang Liang 梁建章, a research professor of applied economics at Peking University, renowned for his focus on China's shifting demographics. He is also the co-founder & chairman of Ctrip, a leading online travel service provider.

James Liang's views have consistently garnered attention both domestically and internationally. I first encountered his work through Zichen Wang, with whom I co-translated an article by Liang last year on China's declining population.

In today's article, Dr. Liang begins by discussing the transition of Tokyo government employees in Japan to a four-day workweek. He then notes that in China, diversified work models, including a four-day workweek, could boost birth rates, employment rates, and domestic demand together — three areas that China urgently needs to strengthen.

Although I believe that proposing a four-day workweek is still too idealistic and somewhat radical for China at present, this advocacy is highly beneficial — it may, at least, facilitate the implementation of the five-day workweek in China.

It just occurred to me what Lu Xun, one of China's greatest modern writers in the 20th century, wrote in his essay "Silent China 无声的中国":

中国人的性情是总喜欢调和,折中的。譬如你说,这屋子太暗,须在这里开一个窗,大家一定不允许的。但如果你主张拆掉屋顶,他们就会来调和,愿意开窗了。没有更激烈的主张,他们总连平和的改革也不肯行。

By temperament the Chinese love compromise and a happy mean. For instance, if you say this room is too dark and a window should be made, everyone is sure to disagree. But if you propose taking off the roof, they will compromise and be glad to make a window. In the absence of more drastic proposals, they will never agree to the most inoffensive reforms.

Dr. Liang shared the original piece on his Wechat Blog today, and I translated it.

梁建章:四天工作制是否可行?

James Liang: Is a Four-Day Workweek Feasible?

Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike recently announced plans to allow Tokyo Metropolitan Government employees to work four days a week starting in April next year, as long as they accumulate a total of 155 working hours over a four-week period. This flexible arrangement is designed to address the persistently low fertility rate and support professional women in balancing work and parenting responsibilities. Additionally, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government plans to offer more childcare conveniences for employees with children in elementary school (third grade or below), including options for later arrivals and earlier clocking out.

Data from Japan's Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare reveals that in 2023, Japan’s number of newborns was 727,000, and the total fertility rate dropped to just 1.20 --both representing the lowest figures ever recorded. Japan was once one of the world’s most dynamic economies, with an average annual GDP growth rate exceeding 8% from the 1950s to the 1980s. However, starting in the 1990s, as the young population continued to decline, Japan's economic growth stagnated, with per capita GDP falling from 21% higher than that of the United States in 1991 to just 41% of the U.S. figure by 2023.

In an effort to boost the fertility rate, Japan has introduced a variety of measures to encourage childbirth, including birth subsidies, childcare services, and workplace support. The four-day workweek policy introduced by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government is an example of the collective efforts by governments at all levels in Japan to address the country's low fertility crisis. While this policy is currently limited to Tokyo Metropolitan Government employees and has a minimal direct effect on the national fertility rate, it serves as a positive and exemplary model for broader Japanese society.

In recent years, China's low fertility rate has become even more pronounced than Japan's. In 2023, China’s fertility rate was around 1.0, significantly lower than Japan's. The number of newborns in China dropped from 18.83 million in 2016 to 9.02 million in 2023, halving in just seven years, while Japan took 41 years to experience a similar decline. It can be expected that the economic downturn caused by the low fertility rate will be more severe and rapid in China than in Japan.

However, China's current efforts to encourage childbirth still lag behind Japan's significantly. According to the new birth support policies recently announced by the State Council, China plans to take actions in areas such as birth subsidies, tax reductions, housing support, and the expansion of childcare services. Additionally, there is hope that implementing more flexible work arrangements to ease childcare pressures will become a key component of fertility support measures.

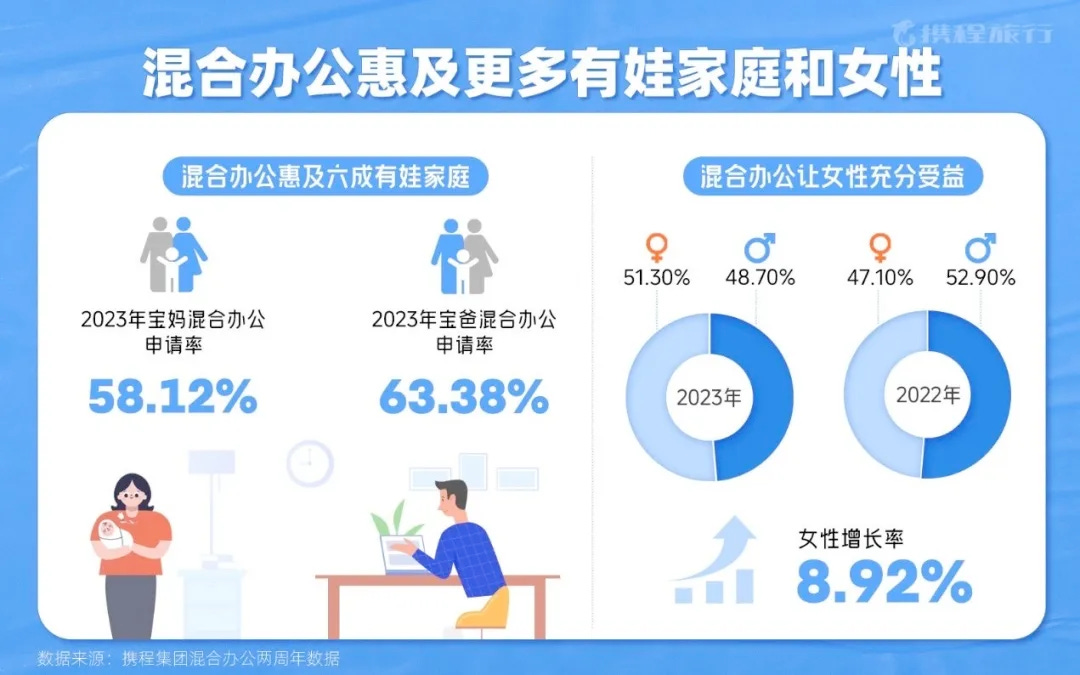

Since February 2022, Ctrip, an online travel service provider led by CEO James Liang, has allowed nearly 30,000 employees to work from home on Wednesdays and Fridays each week. This "3+2" flexible working model has not only maintained work efficiency but also significantly improved employee satisfaction. The hybrid work model reduces commuting time, enabling employees to better balance work and family responsibilities. It also offers more opportunities for parents to spend time with their children, thereby easing childcare pressures. It is hoped that this model will be adopted by more employers.

The title of this image is “Hybrid Work Benefits More Families with Children and Women.”

We also suggest that relevant authorities consider implementing a spring break system for primary and secondary school students. This could involve reallocating approximately one week from the summer or winter holidays to provide a spring break around the "May Day" holiday. Depending on how the spring break system is received, authorities can then gradually consider introducing an autumn break as well.

We also propose that each time a family has a new child, parents should receive an extra week of leave each year. The policy should also encourage paid leave and support travel benefits. We recommend allowing parents to choose their vacation time based on their work schedules, aligning it with the students' spring break. This would help prevent overcrowding of holidays during the winter and summer holidays.

Additionally, we suggest piloting a four-day workweek in certain qualified employers. For example, under relevant regulations, employees could be allowed to switch from a traditional 5×8 work schedule to a 4×10 schedule as needed. Based on the outcomes, a decision can be made on whether to further expand this practice. The implementation of the two-day weekend system in China in 1995 significantly enriched the weekend lives of the Chinese population, boosted domestic demand and consumption, particularly in the service industry, and to some extent alleviated the employment pressures caused by the layoffs of state-owned enterprise employees at that time (late 1990s).

Currently, the economic environment in China is significantly different from that of 1995. However, the idea of a four-day workweek remains highly relevant. Even if total working hours remain unchanged, a four-day workweek, as opposed to a five-day one, can substantially reduce commuting time and provide employees with longer periods of uninterrupted leisure. More importantly, excessively long working hours have become a growing feature of societal "involution 内卷" in China and are widely criticized by public opinion. Implementing pilot programs of four-day workweek on a limited scale can help assess its actual impact, shift the benchmark for working hours, create a demonstrative effect, and communicate to society the need for reduced working hours.

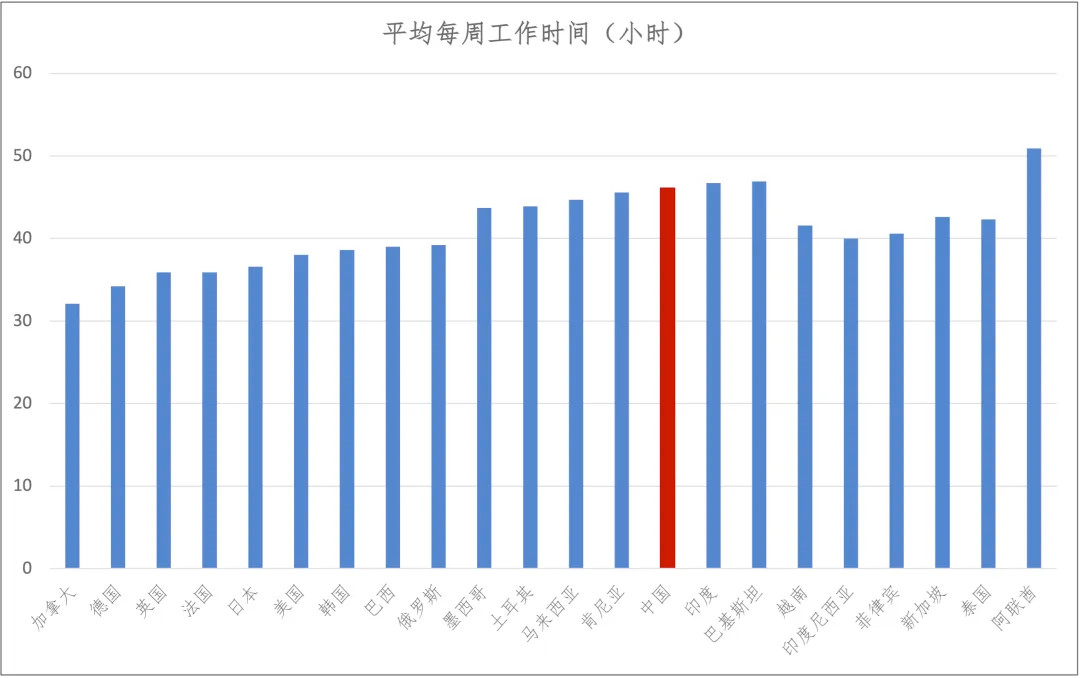

According to the latest data from the International Labour Organization, the average weekly working hours for employees are as follows: China averages 46.1 hours; India, 46.7 hours; Pakistan, 46.9 hours; Vietnam, 41.6 hours; Indonesia, 40.0 hours; the Philippines, 40.6 hours; Malaysia, 44.7 hours; Singapore, 42.6 hours; Thailand, 42.3 hours; Japan, 36.6 hours; South Korea, 38.6 hours; the United Kingdom, 35.9 hours; France, 35.9 hours; Germany, 34.2 hours; the United States, 38.0 hours; Canada, 32.1 hours; the United Arab Emirates, 50.9 hours; Brazil, 39.0 hours; Mexico, 43.7 hours; Russia, 39.2 hours; Turkey, 43.9 hours; and Kenya, 45.6 hours.

The title of this chart is “Average Weekly Working Hours (Hours) by Country.” The red bars represent China.

Based on these data, it is evident that developed countries have significantly lower average working hours compared to developing nations. China's average working hours not only exceed those of developed countries but are also notably higher than those of other nations with similar levels of development, ranking just below South Asian and some Middle Eastern countries.

The ultimate goal of economic development is to achieve greater economic output with less labor input. With preferences for both leisure and income, as labor productivity increases, the average working hours in society should naturally decrease. This is supported by both cross-country comparisons and longitudinal trends in average working hours worldwide. On one hand, more developed countries generally have shorter average working hours, while South Asian and certain Middle Eastern countries -- who employ a large number of foreign workers -- report the longest hours. In contrast, European and American nations typically have the shortest. On the other hand, average working hours are decreasing in most countries. For instance, a survey by Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications revealed that in 2022, Japan's average weekly working hours per capita had decreased by 6.8% compared to 2013.

Despite China's continuously increasing labor productivity and rising GDP per capita, the average working hours have been steadily rising. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, the average weekly working hours for employees in national enterprises was 46 hours in 2019, which increased to 48.9 hours in 2023. This is significantly higher than the State Council's prescribed 40-hour workweek and exceeds Labor Law's provision limiting weekly working hours to no more than 44 hours.

One significant reason behind this trend is that the long-term low fertility rate, particularly the recent drastic decline in birth rates, has lowered expectations for economic growth, resulting in a relatively sluggish economy. Additionally, advancements in technology, especially the development of artificial intelligence, have intensified employment difficulties. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, in October 2024, the unemployment rate among the urban workforce aged 16-24, excluding students, was 17.1%. This severe employment situation, in turn, exacerbates workplace competition and societal involution, compelling employees to accept longer working hours. These phenomena impose a double burden on fertility rates: unemployed young people hesitate to marry and have children due to a lack of expected income; employed individuals face workplace pressures and job insecurity, pushing them to extend their working hours, which naturally makes it difficult to have larger families.

However, the situation where a large number of young people are unable to find jobs while those who are employed are working increasingly longer hours appears contradictory, suggesting that improvements in policy and mechanisms could potentially alleviate these issues. According to the aforementioned data from the International Labour Organization, in 2023, the average weekly working hours for employed individuals in China was 46.1 hours, which is 26% longer than Japan's 36.6 hours. If total working hours across society were to remain unchanged, reducing the average working hours of China's employed population to Japan's level would require a 26% increase in China's employed population. Therefore, theoretically, lowering the average working hours could improve the employment rate. By providing expected income to new employees and reducing working hours for those already employed, this approach could simultaneously enhance fertility rates among both groups.

Why do employers tend to extend the working hours of current employees rather than hire new staff? This can be attributed to three primary reasons: first, economic downturns make the job market increasingly unfavorable for job seekers and employees; second, the fixed costs associated with hiring new employees, such as benefits and training, are prohibitively high; and third, the enforcement of labor laws regarding statutory working hours and overtime pay is inadequate.

In response to these challenges, making parenting a financially viable endeavor by providing substantial child-rearing allowances to parents is crucial. We propose the following subsidies: a monthly allowance of 1,000 yuan (around 140 USD) for each first child, 2,000 yuan for each second child, and 3,000 yuan for each third child and beyond. Additionally, we recommend a 50% reduction in social security contributions and income tax for parents of the first and second children, and complete exemption from social security and income tax for parents of the third child and above. If these subsidies are extended from birth until the child reaches 18 years of age, the total cost is estimated to account for 2% to 5% of GDP. Future funding levels should be adjusted based on changes in fertility rates. Considering the urgent need to expand domestic demand in China's economy, we also propose a one-time cash subsidy of 100,000 yuan per child. This measure would not only stimulate consumer spending but also boost overall confidence in the economy.

As long as the subsidies are comparable to the income from regular employment, many people would temporarily leave the workforce to focus on parenting. This would significantly alleviate employment pressure and enhance the bargaining power of job seekers and employees in both the labor market and the workplace, thereby increasing the employment rate and reducing workplace competition. For newly hired employees, policy-based reductions in welfare expenses and subsidies for training can be provided to employers to lower the fixed costs of hiring new staff. For existing employees, strict enforcement of labor laws regarding working hours and overtime pay is necessary, increasing the costs for employers to extend working hours. These measures are conducive to shortening the average working hours.

Some people are concerned that reducing average working hours might lower China's international competitiveness and slow down economic development. However, in reality, despite facing trade wars and technological suppression initiated by the United States, the international competitiveness of Chinese products has been steadily strengthening. In the first three quarters of this year, China's trade surplus reached a historical high, and industries such as new energy, electric vehicles, and even mature chip manufacturing have become strong sectors in the country. Against the backdrop of China's growing technological and industrial strength, appropriately reducing working hours will not significantly diminish the competitiveness of Chinese products in the international market. Domestically, China faces economic challenges such as relative overcapacity and a clear shortage of consumption, and extending working hours would only exacerbate these issues.

It can be argued that the currently excessive working hours are not an inherent requirement of macroeconomic development, nor a widespread choice based on leisure or income preferences. Instead, they are a "theater effect" resulting from an economic downturn. The so-called theater effect refers to a situation where, in a theater, everyone originally sits down to watch a performance, but suddenly one audience member stands up to watch, forcing those around them to also stand up to see the show, resulting in the entire audience standing rather than sitting. While everyone becomes more tired, the viewing experience itself does not improve. Eliminating the theater effect requires the establishment and enforcement of common rules.

According to Article 36 of China's current Labor Law, the state enforces a working hour system that limits workers to a maximum of eight hours per day and an average of 44 hours per week. Additionally, Article 3 of the "State Council's Provisions on Employees' Working Time" stipulates that employees should work eight hours daily and forty hours weekly. However, in practice, the working hours of employed individuals in China often exceed these standards, with some private enterprises failing to provide even one day off per week. Strictly enforcing these regulations, along with the trial implementation of a four-day workweek, is expected to effectively address the issue of excessively long working hours. It would promote a better balance between consumption and production capacity, while also helping to enhance fertility rates.

In the long term, advancements in technology, particularly the development of artificial intelligence, will further increase labor productivity, reducing the necessity for prolonged working hours. Consequently, it is feasible to further shorten the workweek from five days to four. Currently, Iceland has fully adopted a four-day workweek, and some companies in Japan and Western European countries are also experimenting with this model. Technological progress leads to increased efficiency, meaning that society can achieve greater utility with less labor input. Work is merely the cost of obtaining utility, and naturally, this cost should be minimized. If artificial intelligence can replace many human jobs, humans can appropriately reduce their working hours, thereby having more time to raise children, engage in innovative endeavors, or simply enjoy life. Ultimately, the purpose of economic development is to enable people to live more comfortably and with greater dignity, rather than working harder or becoming the world's worker bees at the expense of reproduction and personal well-being. Enditem